Pietro Mussini: A habitat of an interlocked nature, by Franco Torriani

(published in book form by Edizioni Diabasis, Reggio Emilia, Italy, 2010)

(English translation by Julian Delens)

How far can an artistic practice really produce, and place in a given space and time, place-unrelated objects (in respect to a given place), it’s an underlaying matter that enlivens most of Pietro Mussini’s creative path. It’s a matter of assigning to who is passing by the activation function for these constituent elements, if you wish these objects, by means of light impulses, sounds, interfaces. Within this combination that, with different intensity and frequence (example: light and sound), joins presentation and representation, what matters is the focus on a portion of space. The duration, according to Mussini, «… corresponds to the persistence on the retina, only within the duration of the neuronic experience». An approach, at least partially, neuroaesthetic? Yes, both as for the real interest he nurtures for the scientific aesthetics tradition and as for the ‘neurology of movement art’, to recall an illustrious definition, which has attracted him especially in recent years. The most sensitive emotional aspects of experience are, in fact, one of the clues, of Mussini’s works even previous to conception and execution. These next to those, more on the long period and never left off, on the visual perception, on the relation between visible and invisible, on light/sound/movement, on the human/machine, machine/machine, materials, arts/design relations. Thus Arnheim, Huxley, Merleau-Ponty, together with Lamb and Zeky1.

Quanto possa davvero una pratica artistica produrre, e posizionare in uno spazio e in un tempo, oggetti indifferenti al luogo (a un luogo dato), è una questione sotterranea che anima buona parte del percorso creativo di Pietro Mussini. Si tratta di investire chi passa della funzione di attivare questi elementi compositivi, volendo questi oggetti, mediante impulsi luminosi, suoni, interfacce. In questa combinazione che, con diverse intensità e frequenze (esempio: luminose e sonore), riunisce presentazione e rappresentazione, quello che conta è la messa a fuoco di una porzione di spazio. La durata, per Mussini, «… è quella della persistenza retinica, nella sola durata dell’esperienza neuronale». Un approccio, almeno in parte, neuroestetico? Sì, sia per l’interesse reale che egli prova per la tradizione dell’estetica scientifica, sia per quella ‘neurologia dell’arte del movimento’, per evocare una definizione illustre, che l’ha attirato specie in anni recenti. Gli aspetti emotivi, più sensibili, dell’esperienza sono, infatti, una delle chiavi di lettura, ma prima ancora di progettazione e realizzazione, delle opere di Mussini. Questi accanto a quelli, più di lungo periodo e mai smessi, sulla percezione visiva, sul rapporto fra visibile e invisibile, su luce/suono/movimento, sui rapporti umani/macchine, macchine/macchine, materiali, arti/design. Arnheim, Huxley, Merleau-Ponty, dunque, con Lamb e Zeky1.

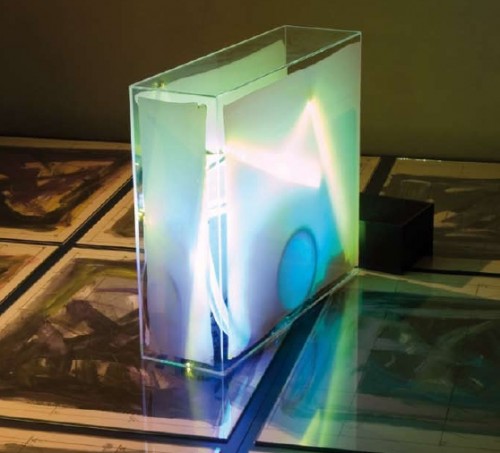

Mediazioni di paesaggio, 1999/2008

scultura evento composta da:

caleidoscopio, elettronica, LED rgb,

fibre ottiche

count down, sintesi vocale

planimetrie, vernici, vetro, plotter

cm 500 x 560 x 160

Mussini is among those artists that, as he writes, «… intends to take part in more memories, in more contemporaries, in more meats – as Merleau-Ponty would say –, in more artifices…». Material and shapes are important but, in his intentions, the desired sequence to be perceived by those who meet his works is the one of «an emotional urging that foreruns the identification of shapes and materials».

Mussini è fra quegli artisti che, come scrive, «… intende partecipare a più memorie, a più contemporaneità, a più carni – per dirla alla Merleau-Ponty –, a più artifici…». Materiali e forme sono importanti ma, nelle sue intenzioni, la sequenza desiderata per chi incontra le opere è quella di «una sollecitazione emozionale che preceda il riconoscimento di forme e materiali».

Mediazioni di paesaggio, 1999/2008

scultura evento composta da:

caleidoscopio, elettronica, LED rgb,

fibre ottiche

count down, sintesi vocale

planimetrie, vernici, vetro, plotter

cm 500 x 560 x 160

It’s useful at this point to mention those mirror-neurons that, quoting Andrea Pinotti, ‘discharge’ when «… a monkey observes another monkey, or a human being, grasping an object, as if it was carrying out the action itself». An attractive hypothesis, turning again to Pinotti, would be the one for which, in front of a work of art, our mirror-neurons would ‘start shooting’ «… as if we were creating it». The path is arduous, but not lacking of fascination and the empathy concept becomes a directional founding point. Mussini is attentive to the research, undergoing in these years, on the emotive, or emotional, response to the arts. It’s the field just mentioned, on the role which the neurosciences have in connecting the works with the emotional responses. Winning, in this respect, is the research of authors such as David Freedberg and Vittorio Gallese2.

Utile qui accennare a quei neuroni-specchio che, come scrive Andrea Pinotti, ‘scaricano’ quando «… una scimmia osserva un’altra scimmia, o un essere umano, afferrare un oggetto, come se fosse essa stessa a eseguire l’azione». Un’ipotesi suggestiva, riprendo ancora Pinotti, sarebbe quella in cui, davanti a un’opera d’arte, i nostri neuroni-specchio ‘sparassero’ «… come fossimo noi stessi a eseguirla». La strada è impervia, ma non priva di fascino e il concetto di empatia diventa un punto fondante di orientamento. Mussini è attento alle ricerche, in corso in questi anni, sulla risposta emotiva, o emozionale, alle arti. È il campo accennato poc’anzi, sul ruolo che hanno le neuroscienze nel collegare opere e risposte emotive. Accattivante, in proposito, la ricerca di autori quali David Freedberg e Vittorio Gallese2.

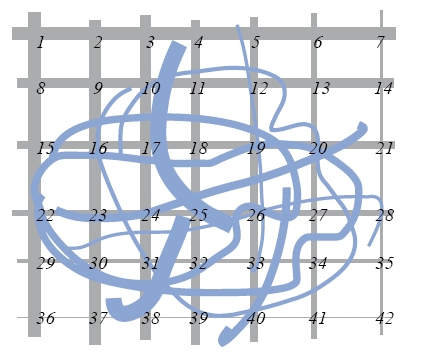

Ortogonali e asimmetrici, 2009

disegni digitali, dimensioni in pixel

The garden, besides being a project, is a program which Mussini has had for years. A garden which, in its essence of closed, bounded place, is quite paradoxically related with an almost visionary idea of scenery. Visionary and interdisciplinary. The garden is a place where, in time, the artist and author – these are his words – is apt to split himself in respect to the manyfold, to the interdisciplinary. The required condition to «… unveil the research sceneries on the human and in the human, and in nature…». The act, other recurrent concept, is indeed the human one, I should say ‘of the living’, and is also the pure ‘mechanical act’3: «… both the humans as well as the machines offer acts and relations».

Il giardino, oltre a un progetto, è un programma di Mussini da anni in corso. Giardino che, nella sua essenza di luogo chiuso, delimitato, è in relativa paradossale relazione con un’idea quasi visionaria di paesaggio. Visionaria e interdisciplinare. Il giardino è il luogo dove, nel tempo, l’artista e autore – sono parole sue – tende a suddividersi al molteplice, all’interdisciplinare. Condizione necessaria per «… svelare paesaggi di ricerca sull’umano e nell’umano, e nelle nature…». Il gesto, altro concetto ricorrente, è sì quello degli umani, sarei per dire ‘del vivente’, ed è anche il puro ‘gesto meccanico’3: «… sia gli uomini che le macchine offrono gesti e relazioni».

Mediazioni di paesaggio, 1999/2008

scultura evento composta da:

caleidoscopio, elettronica, LED rgb,

fibre ottiche

count down, sintesi vocale

planimetrie, vernici, vetro, plotter

cm 500 x 560 x 160

As the garden takes shape, as for its digital production aspect, «… the synthetic images of flowers, fields, gardens (…) don’t form the work itself – as Gianna Maria Gatti points out in an intriguing comparison between Pietro Mussini’s gardens and Katsuhiro Yamaguchi’s –, but a transitional moment…». Thus, it’s a matter of reworking nature, studying its uncountable formal, sound, expressive combinations, «… to graphically build what will be made concrete as a sculpture». Planimetria di una messe (Planimetry of a Field), is an artificial field with endlessly repeatable crops, with an incorporated led. It is sensorially sensitive to external factors, from people’s movement to the temperature and to the air, and it is a decisive computer ‘module’ for his artistic path which dates back to 1986 4.

Sul divenire del giardino, per la sua parte di produzione digitale, «… le immagini di sintesi di fiori, campi, giardini (…) non costituiscono l’opera in sé – rileva Gianna Maria Gatti in un intrigante confronto fra i giardini di Pietro Mussini e quelli di Katsuhiro Yamaguchi –, ma un momento di passaggio…». Dunque, si tratta di rielaborare la natura, studiarne innumerevoli combinazioni formali, sonore, espressive, «… di costruire graficamente ciò che si concretizzerà in scultura». È del 1986 la realizzazione al computer di un ‘modulo’ decisivo nel suo percorso artistico: Planimetria di una messe, un campo artificiale con messi ripetibili all’infinito, con un led incorporato, sensorialmente sensibile ai fattori esterni, dal movimento delle persone alla temperatura e all’aria4.

The aim is not the illusory one of controlling nature, but rather to work on a ground that, as much as these terms can be conventional, is both natural and artificial. Even in his most design-based practices, Mussini proposes himself as a temporary author, more so, in his rather cryptic definition of author’s authorial authority. It’s in these practices after all that his drive to compare intuition, environmental interferences, historical sedimentation, knowledge practices is best recognized.

Lo scopo non è quello illusorio di controllare la natura, bensì di lavorare su un terreno che, per quanto siano convenzionali questi termini, è naturale e artificiale. Anche nelle sue pratiche più fondate sul design, Mussini si propone come autore transitorio, anzi, nella sua un po’ criptica definizione di autorità autorale di un autore, è poi in queste che si nota meglio la sua spinta a confrontare intuizione, interferenze ambientali, sedimentazione storica, pratiche della conoscenza.

His unusual definition of inauthoriality that, in the various operational trajectories, includes «machine mind’s images…», archetypes, kinetic, sound, chromatic effects, helps, with a pinch of cynicism, to shift the activity, and the responsibility of author, the auctor, towards a realistic artificial imagery. Temporary, but also constantly in balance between transitivity and intransitivity, he prefers to work on the processes that simulate the living without turning to techniques which alter it directly. The consideration for the new metamorphosis generated by the new media’s flow, also due to incessant organic and mechanic recombination, is right on the mark, also as an inter-generational path. Bruce Clarke, in a recent text, talks about this while dealing with post-human metamorphosis. A debated matter… Forty years after Jashia Reichart’s seminal exhibition “Cybernetic Serendipity” (1968) in London, it’s stimulating, in respect to works as these, to consider the question raised, a few months ago, in the Yasmin network in Cybernetics Serendipity Redux: «what is new in cybernetics, and how this can inform (and inspire) art. And what is new in art, and how this can inform (and inspire) cybernetics…»5.

La sua singolare definizione di inautoralità che, nelle varie traiettorie operative, comprende «immagini della mente delle macchine…», archetipi, effetti cinetici, sonori, cromatici contribuisce, con una punta di cinismo, a spostare l’attività, e la responsabilità, dell’autore, l’auctor, a un realistico immaginario artificiale. Transitorio, ma anche in bilico continuo fra transitività e intransitività, preferisce lavorare sui processi che simulano il vivente senza ricorrere a tecniche che lo modificano direttamente. Puntuale, anche come percorso intergenerazionale, la presa in considerazione delle nuove metamorfosi generate dal flusso dei nuovi media, anche per effetto del ricombinarsi incessante di organico e meccanico. Bruce Clarke, in un suo testo recente, ne parla trattando di metamorfosi post-umane. Argomento dibattuto… A quarant’anni dalla seminale mostra di Jashia Reichart a Londra, “Cibernetic Serendipity” (1968), è stimolante, davanti a opere come queste, porsi la questione sollevata, qualche mese fa, sulla rete Yasmin in Cybernetics Serendipity Redux: «Che cosa c’è di nuovo nella cibernetica, e come questo può informare (e ispirare) l’arte. E che cosa c’è di nuovo nell’arte, e come questo può informare (e ispirare) la cibernetica…»5.

Of no less importance for Mussini, is the continuous self-renewal, not remaining «… in a mere object reproduction or simulation status». According to him the artist is a BIOlogical subject6 who confronts and dialogues with sensitivities that belong to manyfold natures, a subject that poetically «… ventures aesthetic variations which belong to the living…». In a time of diluted and diffused aesthetics, borrowing it from Benjamin and from Yves Michaud’s acute analysis, here returns the indication of the easthetics of distraction. Very pertinent is the notion of a de-aestheticised experience – I am drawing on Michaud – «… similar to the visual and bodily one, we have of architecture». It’s the ‘distracted’ experience of the user, or of the loafer, «… as opposed to the one of the connoisseur and of the initiate»7.

Non di minore importanza, per Mussini, è il rinnovarsi di continuo, non rimanendo «… in uno stato di mera riproduzione o simulazione delle cose». L’artista, per lui, è un soggetto BIOlogico6 che confronta e dialoga con sensibilità appartenenti a più nature, un soggetto che poeticamente «… azzarda variazioni estetiche che appartengono al vivente…». In un tempo di estetica diluita e diffusa, mutuandola da Benjamin e dall’acuta analisi che ne fa Yves Michaud, mi torna qui l’indicazione di estetica della distrazione. Molto pertinente la nozione di un’esperienza de-estetizzata – riprendo Michaud – «… analoga a quella visuale e corporale, che facciamo dell’architettura». È l’esperienza ‘distratta’ dell’utilizzatore, o del bighellone, «… opposta a quella del conoscitore e dell’iniziato»7.

Experience where the representation, as Mussini reminds us, «… has never been resolved in itself, but only in what is perceived as a primary significance, but also in what it suggests, in manifold secondary levels…». It’s the cross-reference to manifold representations, a kind of metonymy that eases the illusionism of a strictly metaphoric matter.

Esperienza dove la rappresentazione, ricorda Mussini, «… non è mai risolta in se stessa, solo in ciò che è percepito come una significazione primaria, ma anche in ciò che suggerisce, in livelli secondari molteplici…». È il rimando a più rappresentazioni, a una sorta di metonimia che, per lui, tempera l’illusionismo di un discorso strettamente metaforico.

Both within the confrontation between presence and representation, reproposed in recent years thanks to the relation between arts and life sciences, as within the one more linked to the twentieth century arts, taken in terms of contiguity and similarity, Mussini tends to a complex balance between metonymy and metaphor. The relation between presence and representation is not for him alien to the present analysis of philosophers such as Gumbrecht and Runia, and to the theorisations – especially on the bio-technological front – of an author such as Hauser. He remains also sensitive to a call to distant times, I am thinking, for example, to the nice essay which Menna wrote in the last quarter of the past century, where the confrontation between two basic language polarities – according to Jakobson – : metonymic and metaphoric stands out8.

Nel confronto fra presenza e rappresentazione, riproposto in questi anni in virtù del rapporto fra arti e scienze della vita, sia in quello più legato alle arti del Novecento, preso in termini di contiguità e similarità, Mussini tende a un complesso equilibrio fra metonimia e metafora. La relazione fra presenza e rappresentazione non è per lui estranea alle analisi attuali di filosofi quali Gumbrecht e Runia, e alle teorizzazioni – in particolare sul fronte biotecnologico – di un autore come Hauser. Egli resta anche sensibile a un richiamo a tempi più lontani, penso ad esempio al bel saggio che Menna scrisse nell’ultimo quarto del secolo scorso, dove risalta il confronto fra le due polarità fondamentali del linguaggio – secondo Jakobson –: la metonimica e la metaforica8.

Not only, reworking what Menna wrote, contiguity and similarity, i.e. the two language polarities mentioned above, are present in Mussini but there is also a continuous attention towards the relation between growth and form. From here stems his focus for how much the life sciences influence nowadays the ‘historical’ relation between art and sciences (and techno-sciences). In order to have some previous and, relatively distant, example one has to refer to the supporting themes of the English exhibitions of Richard Hamilton, “Growth and Form” (1951) and “Man, Machine and Motion” (1955). The title of the first one, by the way, cross-references to an explosive, for its times (1917), text: On Growth and Form, written by D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson, the Scottish biologist known for his physical and mathematical approach to the organic forms. It’s information, at last, that the work contains, ‘instruments’ as Pietro Mussini defines them, «… instruments of nature – the meaning and the reason of acting… –; instruments of speculation – anthropological history and position… –; critical instruments – knowledge surveys that own the subjects involved… –»9.

Non solo, rielaborando quanto scrisse Menna, la contiguità e la similarità, ovvero le due polarità del linguaggio ricordate sopra, ma è presente in Mussini anche un’attenzione continua per il rapporto fra crescita e forma. Da qui l’attenzione per quanto le scienze della vita influenzano oggi il rapporto ‘storico’ fra arti e scienze (e tecnoscienze), così come per qualche precedente esemplare, e relativamente lontano, si pensi ai temi portanti delle mostre inglesi di Richard Hamilton, “Growth and Form” (1951) e “Man, Machine and Motion” (1955). Il titolo della prima, fra l’altro, rimanda a un testo per i tempi dirompente (1917), On Growth and Form, scritto da D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson, il biologo scozzese noto per il suo approccio fisico e matematico alle forme organiche. Sono, infine, dati che l’opera contiene, ‘strumenti’ come Pietro Mussini li definisce, «… strumenti della natura – il senso e il perché del fare… –; strumenti della speculazione – storia e collocazione antropologica… –; strumenti critici – casistiche della conoscenza che possiedono i soggetti coinvolti… –»9.

Notes

1. The article by Matthew Lamb and Semir Zeki, The neurology of Kinetic Art, appeared in «Brain», n. 117, in 1994, quoted in the writing by Andrea Pinotti, Neuroestetica: una nuova disciplina dalle radici antiche (Neuro-aesthetics: a new discipline with ancient roots), Department of Philosophy, Università degli Studi di Milano (in «Sistema Università, La Statale Informa», n. 2, year IV, April 2006). Pinotti’s writing offers an interesting and concise outline of Neuro-aesthetics and of the neuro-phisiologic basis supplied by the discovery of the mirror neurons, thanks to Giacomo Rizzolatti and to a group of researchers of the University of Parma.

1. L’articolo di Matthew Lamb e Semir Zeki, The neurology of Kinetic Art, comparve in «Brain», n. 117, nel 1994, citato nello scritto di Andrea Pinotti, Neuroestetica: una nuova disciplina dalle radici antiche, Dipartimento di Filosofia, Università degli Studi di Milano (in «Sistema Università, La Statale Informa», n. 2, anno IV, aprile 2006). Lo scritto di Pinotti presenta un panorama interessante e conciso della neuroestetica e della base neurofisiologica fornitale dalla scoperta dei neuroni-specchio, grazie a Giacomo Rizzolatti e al gruppo di ricercatori dell’Università di Parma.

2. Among the authors that deal with the relations between art and brain, to use a current terminology, I would like to point out David Freedberg’s approach, an art historian specially alert to the neurobiological impact on the physical and emotional reactions to the works of art. Cf., by David Freedberg (Department of Art History and Archeology, Columbia University, New York) and by Vittorio Gallese (Department of Neuroscience, University of Parma, Parma), Motion, emotion and empathy in esthetic experience, www.sciencedirect.com, 2007, Elsevier Ltd. (Available on line, 7 March 2007). Freedberg and Gallese, these for «… their researches (laid out) on the neural basic of the inter-subjective experience» are among the authors pointed out by Andrea Pinotti, op. cit., note 1.

2. Fra gli autori che si occupano dei rapporti fra arte e cervello, per usare una terminologia corrente, segnalo l’approccio di David Freedberg, uno storico dell’arte particolarmente attento all’impatto neurobiologico sulle reazioni fisiche e emozionali, alle opere d’arte. Cfr., di David Freedberg (Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University, New York) e di Vittorio Gallese (Department of Neuroscience, University of Parma, Parma), Motion, emotion and empathy in esthetic experience, www.sciencedirect.com, 2007, Elsevier Ltd. (Available on line, 7 March 2007). Freedberg e Gallese, questi per «… le sue ricerche (impostate) sui fondamenti neurali dell’esperienza intersoggettiva» sono fra gli autori indicati da Andrea Pinotti, op. cit., nota 1.

3. The inverted commas are by Pietro Mussini.

3. La virgolettatura è di Pietro Mussini.

4. In 2009, the AVINUS Verlag/Press of Berlin (http://verlag.avinus.de/) published Gianna Maria Gatti’s book The “Technological Herbarium” in both English and German editions (the original book is L’Erbario Tecnologico, CLUEB, Bologna 2005). The Italian-to-English translation is by Alan N. Shapiro, and the Italian-to-German translation is by Dr. Helene Harth.

4. Gianna Maria Gatti, L’Erbario Tecnologico – La natura vegetale e le nuove tecnologie nell’arte tra secondo e terzo millennio, CLUEB, Bologna 2005.

5. Cybernetic Serendipity Redux, a discussion started on 1st September 2008 in YASMIN, edited by Ranulph Glanville. (Co-sponsor: Leonardo/OLATS). YASMIN is a network of artists, scientists, theoreticians, institutions that cooperate on arts, sciences, technologies around the Mediterranean, http://www.media.uoa.gr/yasmin/. (Inspire) has been added by who is writing.

5. Cybernetic Serendipity Redux, una discussione iniziata il 1° settembre 2008 su YASMIN, a cura di Ranulph Glanville (Co-sponsor: Leonardo/OLATS). YASMIN è una rete di artisti, scienziati, teorici, istituzioni che cooperano su arti, scienze, tecnologie intorno al Mediterraneo, http://www.media.uoa.gr/yasmin/. (Ispirare) è aggiunto dallo scrivente.

6. BIOlogical, as Pietro Mussini in a recent writing of his.

6. BIOlogico, così Pietro Mussini in un suo scritto recente.

7. From the book by Yves Michaud, L’art à l’état gazeux. The subtitle, the literal translation is by who is writing, is approximate: Saggio sul trionfo dell’estetica (Essay on the triumph of aesthetics). Hachette Littératures, Éditions Stock, Paris 2003.

7. Dal libro di Yves Michaud, L’art à l’état gazeux. Il sottotitolo, la traduzione letterale è dello scrivente, è indicativo: Saggio sul trionfo dell’estetica. Hachette Littératures, Éditions Stock, Parigi 2003.

8. Filiberto Menna, La linea analitica dell’arte moderna – Le figure e le icone, (The analytic line of modern art – The figures and the icons), Einaudi, Torino 1975.

8. Filiberto Menna, La linea analitica dell’arte moderna – Le figure e le icone, Einaudi, Torino 1975.

9. Conversation with Pietro Mussini, October 2008.

9. Conversazione con Pietro Mussini, ottobre 2008.

For the exhibitions conceived by Richard Hamilton, “Growth and Form”, ICA, London 1951 and “Man, Machine and Motion”, Hatton Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne and ICA, London 1955, cf. web site Tate online, Richard Hamilton.

Per le mostre concepite da Richard Hamilton, “Growth and Form”, ICA, Londra 1951 e “Man, Machine and Motion”, Hatton Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne e ICA, Londra 1955, cfr. sito Tate online, Richard Hamilton.

Pietro Mussini: Principali esposizioni/Exibitions

1985

La Neomerce, Milano, XVII Triennale

La Biennal, Barcellona

1986

Tout beau, tout néo, Parigi, Centro G. Pompidou

Progetto domestico, Milano, Triennale

1987

Kreative Heimroboter-Haustiere von Morgen Amburgo, Galerie Mobel Perdu

Milanopoesia, Milano, Rotonda della Besana

La caverna elettronica, Torre Pellice, Galleria d’Arte Contemporanea

Premio Marche, Ancona, Mole Vanvitelliana

1988

Personale, Reggio Emilia, Civici Musei

1989

La scultura e la città, Alatri, XXV Biennale Arte Contemporanea

1990

Artefax, Bologna, Galleria d’Arte Moderna

L’intimità tecnologica [Personale], Rimini

Palazzo Gambalunga

1991

Anni ’90, Rimini, Musei Comunali

Extravaganti elettronici, Bari, Tecnopolis

Sinestesie dell’immateriale [Personale], Parma

Galleria Alphacentauri

1992

Electronica, Bologna

Ex convento di San Giovanni in Monte

Mondi armonici, Torino

Ex scuderie di Villa Tesoriera

1993

L’arte alla sfida delle tecnoscienze, Parigi, La Villette

Rentrée, Ancona, Mole Vanvitelliana, Premio Marche

Tecnoscienze, intuizione artistica e ambiente artificiale, Torino, Galleria d’Arte Moderna

1994

Una generazione italiana, Perugia, Rocca Paolina

Itinerari, Bologna, Galleria d’Arte Moderna

Arte, città, tecnologie, Parigi, La Villette

1995

I sensi del virtuale, Torino, Arslab

Oltre la scultura, Padova, Palazzo della Ragione

XVI Biennale Internazionale del Bronzetto

1996

Proposta di una scultura, Prato, Piano regolatore

1997

Ancona, Mole Vanvitelliana, Premio Marche

1998

Arte e scienza, Bologna, Palazzo Re Enzo

1999

Mir-Arte nello spazio, Bolzano, Galleria Civica e Fiera

Avangarden, Parma, Palazzotto Buscherio Sanvitale

2000

Duemila anni luce, Reggio Emilia, Galleria Parmiggiani

2001

(S)Guardo / (EIN)Blike, Milano, Spazio Quid

Tecnologica, Gorla Maggiore (MI), Torre Colombera

2002

Revisioni, Reggio Emilia, Chiostri di San Domenico

2003

Inchiostro indelebile, Roma, MACRO

Enter-invito al futuro, Serra San Quirico, Premio Casoli

2004

Artisti dall’Italia, Olomouc, Galerie G

2005

Parco della scultura, Castelbolognese (RA)

Centro culturale C.etrA

2006

Contro_E_Vento, Ligonchio (RE), centrale idroelettrica

2007

Arte Energia Impresa, Licciana Nardi (MS)

Castello di Terrarossa

2008

Materiale Immateriale, Scala (Salerno), Museo MUSCA

Un habitat di nature interfacciate [Personale]

Scandiano (RE), Rocca dei Boiardo

Nuove sinestesie, Suzzara (MN), 46° Premio Suzzara

2010

XXV Premio Marconi, Bologna, Circolo Artistico

Figure della protezione, Carpi (MO), Palazzo Pio