Gerry Coulter, Sophie Calle and Baudrillard’s “Pursuit in Venice”

by Alan N. Shapiro

- My Friend Gerry

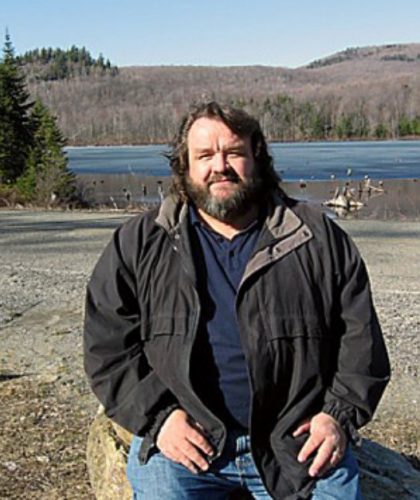

I did not know Gerry Coulter well personally. Yet I have considered him to be my friend. Our intellectual, political, and academic perspectives have been very close to one another. We have been comrades-in-arms, fighting for the same cause. We have both been deeply engaged with Jean Baudrillard’s system of thought. Gerry has helped me a lot, and in many different ways, and over a period of time of more than a decade. He has been greatly supportive of my work. I would not be where I am now, professionally or personally, without this help which I received as a gift from Gerry. I feel a very profound gratitude towards him.

Photo courtesy of International Journal of Baudrillard Studies

- The “Posthumous Representation” of Art

Baudrillard’s relationship to art (and to photography) was one (or were two) of Gerry’s passionate interests. Gerry wrote the entry on “Art” for Richard G. Smith’s Baudrillard Dictionary (Alan Cholodenko wrote the entry on “Photography”).1 Baudrillard was intensely critical of what he called The Conspiracy of Art.2 Art is already finished. It is done. It is over. Dead. Death in Venice, one could say, to metaphorically reference the title of Thomas Mann’s 1923 novella about the sudden demise of a great artist (writer). The character Gustav von Aschenbach is spinning his wheels in his creative work and believes that it is his destiny to travel to Venice and take a suite in the “grand hotel abyss” (a phrase of Georg Lukacs) near the historical casino on the Lido island.

“The reputations of curators,” writes Gerry Coulter in The Baudrillard Dictionary, “are staked on keeping alive the idea of an avant-garde.”3 Art was brought to a conclusion by its most emblematic and ironic twentieth-century avatars such as Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol. “This is not to say that new things did not continue to happen in the arts,” maintains Coulter, “but that it was (mainly because of Duchamp’s influence on countless young artists since the 1950s) a form of ‘posthumous representation’.”4 In Baudrillard’s view, art becomes “transaesthetics”: confused about its own genre boundaries, lacking a conscious reflection on its expressive forms, and on the operation of its cybernetic feedback systems. Art’s ornamental and promotional values radiate in all directions – like greenhouse gases acting on infrared energy – by way of its prodigious works and its multitudinous “interactive” installations, having definitively lost its orientation while swimming for survival in the midst of an omnipresent consumer and design culture where everything is aestheticized. Art is now everywhere (except in art), and therefore nowhere.

New media art, for example, makes the mistake of “coming too close to reality” (Baudrillard) in its high-resolution n-dimensional graphics and its hyper-detailed coded techno-scientific implementations, instead of mounting a challenge to or against media civilization’s “reality.” New media art often becomes indistinguishable from the passionate exploration of all of the audio-visual (and quasi-pre-programmed) possibilities carried out by computer or technology enthusiasts.

“Art is dead” is indeed the primary valid way to understand the contemporary post-art situation, even though many interesting artworks continue to be made. Similarly, the never-ending Persian Gulf War in Iraq and its surrounding countries is primarily a television spectacle for home entertainment (Jean Baudrillard, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place and Paul Virilio, Desert Screen), even though real people die, and infrastructures and vast ecologies get destroyed.5 The war victim deaths are mere “fresh meat” data input for the multimedia global war game entertainment system. President Donald Trump, to mention another analogous example, is mainly a Reality TV game show host (everyday life in America having by now become a “media”; America’s tele-morphosis is everywhere), even though real people and the Earth are suffering from Trump’s policies.

“Art” persists and flourishes as a profitable hyper-industry, with its own inflated pretensions and its self-legitimating prestigious institutions. Baudrillard saw the contemporary art world as being complicit with – and metaphorical of – late semiotic capitalism. He explicitly rejected the New York art scene’s attempted embrace of him as a critical cultural thinker in the 1980s. Baudrillard was always suspicious of any project of “applying” his ideas about simulation, virtuality, hyper-reality, and the orders and precession of simulacra in a “transdisciplinary” or “crossover” way to either art (the New York “Simulationist” or “Appropriation” or Neo-Conceptualist or Neo-Geo artists such as Sherrie Levine, Jeff Koons, and Peter Halley, who claimed that their artworks were “simulacra” against “hyper-reality”: for example, on the level of colors), or architecture (as the Parisian Jean Nouvel endeavored to do in speaking of an alleged “Baudrillardian architecture” in his book-length conversation with Baudrillard called The Singular Objects of Architecture), or even film, as in the case of the Wachowski siblings’ canonization of him as the supposed philosophical inspiration for The Matrix film series.6

In the face of ubiquitous hyper-reality or “integral reality” (Baudrillard), and the beautification of banality, one would have to gesture in a radical artwork towards insignificance, and in such a way that one’s works do not become the simulacrum of this “nullity.” With the advent of the society and technology of virtual reality, we are living inside the image, and in a “giant museum.”7 An artwork or installation intending to demonstrate simulation or seduction can easily descend into being a signifier of the idea of simulation or seduction. Art, for Baudrillard, should essentially be about form and metamorphosis, and form confounds the logic of capitalist-commodity exchange and equivalence, the habitual worldview of consuming a system of semiotic signs. At present, however, writes Baudrillard, “nothing differentiates [art] from technical, advertising, media and digital operations” – for example, the ritualized layout-placing of multi-media elements such as text, image and animations side-by-side, in the reciprocally-neutralizing reduction of the force of singular genres of creative expression to a deceptively uniform informational interface.8

- The Radical Illusion Beyond Art

On the affirmative side of things, Gerry Coulter – as the leading Baudrillard scholar – put a great deal of effort into investigating into and commenting on the creations of those relatively few artists and photographers whom Baudrillard admired as enactors or choreographers of the “radical illusion beyond art.” These practitioners ally themselves objectively with the “vital illusion of the world.” They create artworks, installations and performances which bond “in radical uncertainty” with the world (which is unique and cannot be copied). Their devised “artifices” institute an “impossible exchange between the world and its representation or double” (or at least a recognition of the impossibility of that exchange). This is something which the French poststructuralist thinker both theorized in his writings and practiced in his own photography as “the [technological] writing of light.”9 Art must deconstruct its own aura of authenticity or simulation and seek instead a “superior irony” in a fantastical exceeding of, or commenting on, the consumerist-commodity-form as symbolic-sacred (in a quasi-anthropological sense) rather than critical-nostalgic and sentimental, pursuing an artistic practice first theorized by the nineteenth-century poet Charles Baudelaire. “It [art] must destroy itself as a familiar object and become monstrously unfamiliar.10

Baudrillard-Coulter’s list of “artists beyond art,” however, is surprisingly quite a bit longer than one would expect. By “artists beyond art,” I mean great creators who are already practicing something different from the mainstream currents of art, and whose works need to be interpreted differently from how the “art industry” sees them. Their creations should probably not be understood with the term “art.” In his own variation of a “Baudrillard Dictionary” (a book-length compendium entitled From Achilles to Zarathustra: Jean Baudrillard on Theorists, Artists, Intellectuals & Others), Coulter wrote many entries on individual artists and photographers whose designs and realizations were esteemed by Baudrillard as significant landmarks in this respect.11

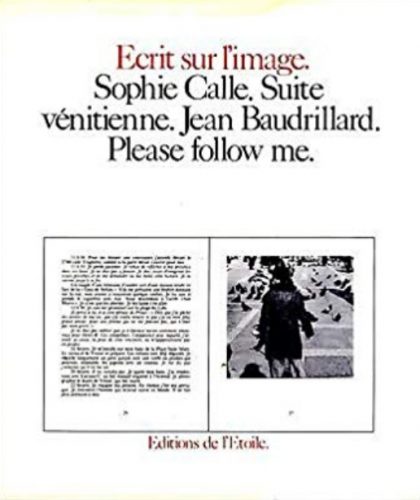

Some of the principal figures are Edward Hopper (the use of light in his paintings), Francis Bacon (whose paintings are “beyond aesthetics” and give form to “the illusion”), Jackson Pollock (of equal stature with Warhol), Mark Rothko (establishes unmediated contact with “the object” or “the fragment”), Enrico Baj (a proto-Situationist and “pataphysician” about whose prints and collages Baudrillard wrote an essay and conducted an interview – they have a “mythical” quality and confront “the monstrous”), Luc Delahaye (on whose “illegal” and hidden-camera photography of Paris Metro riders Baudrillard wrote), Mike Disfarmer (photographer of residents of rural Arkansas in the 1940s), Christo and Jeanne-Claude (the “wrapping” in synthetic fabric and cloth of architectural structures such as the Berlin Reichstag and the Parisian Pont-Neuf bridge, and natural locations such as the New York City Central Park pathways or the coastline near Sydney, Australia, “enoble(s) a form by covering it up”), Charles Matton (Baudrillard and Virilio both wrote essays about his artworks which were miniature experimental spaces or “enclosures” which brought attention to “the illusion” and not to “the reality”), Olivier Mosset (a painter known for his monochrome abstract works about which Baudrillard wrote a catalogue entry), and Sophie Calle (about whose photographic-conceptual-storytelling-performative art projects Baudrillard wrote the essay “Please Follow Me” – also known in modified form as “Pursuit in Venice”).12 And, of course, Duchamp and Warhol.

- Shadowing, Doubling, Following, Tracing

In his entry on Sophie Calle in his systematic collection of Baudrillard’s influences and references From Achilles to Zarathustra, Gerry Coulter writes: “Baudrillard’s ‘Please Follow Me’ appears at the end of Calle’s Suite Vénitienne – a novel in which Calle follows a man (she has met at a party in Paris) to Venice where she continues to secretly follow and photograph him.”13 Calle sets up or forms an other-reflexive relationship of shadowing, doubling, following, and tracing with the unaware human object of her pursuit in the World Heritage Site northern Italian city of canals and bridges.

I will now consider Calle’s Venetian art project about shadowing and doubling as a notable example of that kind of “radical illusion beyond art” project which Baudrillard found to be compelling, and which is consistent with his later philosophy of “radical otherness” and “taking the side of objects,” and which Gerry Coulter emphasized in his important research in Baudrillard Studies.

The relationship of following and tracing enacted by Sophie Calle also inspires me – in terms of a metaphor – in my thoughts and feelings about my relationship to Gerry Coulter.

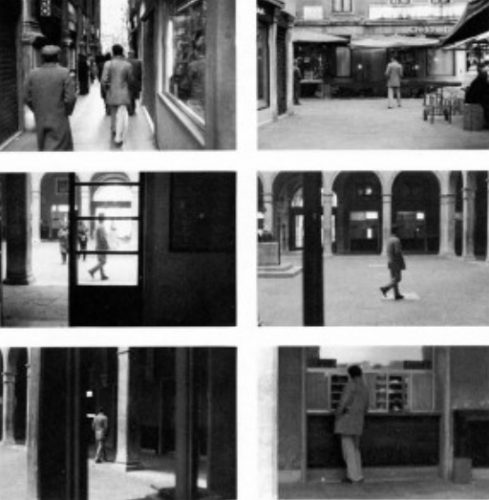

- Sophie Calle and Jean Baudrillard: Pursuit in Venice

Baudrillard writes in “Please Follow Me” or ”Pursuit in Venice”: “One day Sophie decides to add another dimension to this ‘experience’ [of following people in the street at random for one or two hours]. She learns that someone she barely knows is traveling to Venice. She decides to follow him throughout his trip… She has a camera, and at every opportunity, she photographs him, the places he has been, and the places he has photographed.”14 The basic rule or prime directive of the game is that there should be no contact between them.

Sophie Calle, Suite Vénitienne: “Saturday. February 16, 1980. 8:00 A.M. Calle del Traghetto. I am waiting for him. The street is closed-in, narrow, about a hundred meters in length, running from Campo San Barnaba to the dock. It’s used only by its inhabitants and vaporetto [waterbus] passengers. Every five minutes, when a boat arrives, a wave of people streams over the deserted street. If Henri B. leaves the pensione when the street is empty, he won’t escape me. But if he goes out at a crowded moment, I run the risk of missing him.”15 There is a complex intricate psycho-geographical separation and interweaving between places in Venice where tourists go and those places where only Venetian natives go.

Baudrillard: “The other’s tracks are used in such a way as to distance you from yourself. You exist only in the trace of the other, but without his being aware of it.”16 Your itinerary and goal are to become non-identical to yourself, just as there is no one-to-one relationship between signifier and signified in semiotic or “grammatological” (Derrida) linguistics.

Photo © 2010 Alan N. Shapiro

Sophie Calle: “Sunday. February 17, 1980. 8:00 A.M. Calle del Traghetto. I wait as I did yesterday. It’s Sunday, there are fewer people. It’s cold. I resume my coming and goings.”17 Sunday is the day of the weekly cycle when the stage sets collapse for the postmodern Sisyphus, the day when the “why” arises and “everything begins in that weariness tinged with amazement.” (Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus)18

Baudrillard: “Nothing was to happen, not one event that might establish any contact or relationship between them… She photographs him continuously… It is the shadowing in itself that is the other’s double life.”19 The shadow, the specter, the mirror-people, the ghost-people, the spectral individuals.

Sophie Calle: “Monday. February 18, 1980. 8:00 A.M. Calle del Traghetto. It’s freezing out. I patiently resume my comings and goings.”20 Venice is a maze or labyrinth. Venice is a living symbol of all that is cultural and artistic in the Western historical traditions. Venice is a synthesis of all aesthetic forms and literatures. Yet Venice is also beyond history, beyond art, beyond architecture, beyond media, beyond classical sociology, and beyond “the networked society.” All of these “modernist” aggregates – or categorized classes of knowledge-objects – belonging to our “enlightened self-understanding” have been eclipsed and have vanished and ended in Venice.

Photo © 2010 Alan N. Shapiro

And the hyper-modernist cities of New York and Las Vegas are also beyond all of these modernist instances.

Baudrillard: “The city [Venice]… brings back people to the same points, over the same bridges, onto the same plazas, along the same quays. By the nature of things, everyone is followed in Venice; everyone runs into each other, everyone recognizes each other… Venice is an immense palace in which corridors and mirrors direct a ritual traffic. Perfectly opposed to the extensive, unlimited city, Venice has no equal in the inverse extreme except New York (and sometimes, curiously, in this inverse extreme, their charms bear a certain resemblance.)”21 Where beneath the water and in which Venice canal would one find the mouth of the natural-artificial wormhole that would allow one to travel back and forth instantly between Venice and (New York or Las Vegas), and perhaps across decades of time? Wormholes are tunnels that connect two areas of space or time.

Sophie Calle: “Tuesday. February 19, 1980. 10:00 A.M. From the Bar Artisti I watch, turned toward Campo Santa Barnaba, waiting, without conviction, for him to pass. I don’t make much of an effort, I give myself a break – I have seen him.”22 Reward yourself after each accomplishment.

Baudrillard: “Shadowing implies… surprise. The possibility of reversal is necessary to it. One must follow in order to be followed, photograph in order to be photographed, wear a mask to be unmasked, appear in order to disappear, guess one’s intentions in order to have your own guessed.”23 The traces which have been left for me from elsewhere and which I follow. In the precession of the phases of capitalism, we have left the mode of production and the mode of information; we are in the mode of seduction and the mode of disappearance. Photography is itself an art of disappearance. Can other technological “new media art” practices follow in the footsteps of the exemplary “disappearing” act of photography and its principles? (and in a way completely “other” from how the 1980s New York Simulationist artists tried to do it?) We are living a quantum physics sociology of the discovery of the macro-world equivalent of the discovery of the subatomic “virtual” particles that permanently pop into and out of existence.

Gerry Coulter and I had planned to meet soon in Italy – in Milano or Venice – for the next conference on “what is hyper-modernism?” or “what is quantum culture?” – the follow-up to the conference which took place in Paris in April 2016.

The Venice conference on quantum culture will not take place.

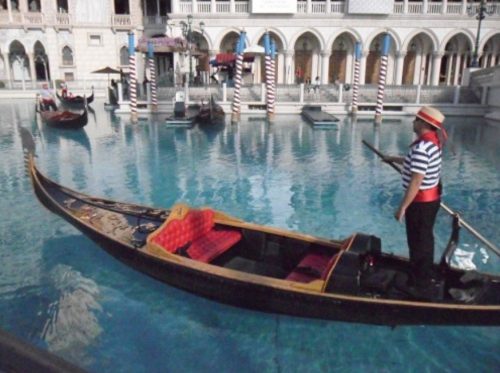

- Venice in Las Vegas

Las Vegas architecture as science fictional simulations of the memorable monuments to human civilization which will be left over after the nuclear war. The Eiffel Tower of Paris. The pyramids of Egypt.

Alan N. Shapiro: It was in Las Vegas where I was able to relive all of my essential European and New York wanderings.

New York City in Las Vegas. Duplicate of Christopher Street and Sheridan Square. The entrance to the number 1 and 9 subway lines. Replications of the Statue of Liberty and the Brooklyn Bridge. Copies of the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building.

After a good night’s sleep at the Marriott Residence Inn on Paradise Road near the Las Vegas Convention Center, we drive to Las Vegas Boulevard South and park the car on level 8 of the parking complex. We descend the elevator that is about to transport us to Venice, Italy.

Photo © 2010 Alan N. Shapiro

The architectural reproduction in Las Vegas of other parts of the world is also an elaborate three-dimensional mirage devised to distract the gambler from the fact that he is being separated from his money. The gambler loses his money in order to win the (copy of the) world.

But this simulation architecture and ambience exceed the intentions of the casino hotel owners. “Learning from Las Vegas” (Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour) today is to learn that Venice is an idea.24 Paris is an idea. New York is an idea. An idea can be expanded and extended. Venice is not restricted to its physical location in the region of Veneto in northern Italy. Embodied semiotics is what makes “reality.” I am physically in Las Vegas but I am “really” in Venice. “Culture has never been anything but the collective sharing of simulacra.” (Jean Baudrillard, Fatal Strategies)25

It’s time for some lunch. The architecture and décor of the Grand Lux Café were inspired by the look and feel of classic Venetian cafes. I will have the Quattro Formaggi or “Four Cheeses” pizza per favore: mozzarella, parmesan, roman, and fontina.

In casino gambling, I have my own prime directive or rules of the game. At each casino that I visit, I win exactly 80 dollars, no more and no less. I play several hands of blackjack and get ahead $40. Then I put the $40 in chips on “red” at a roulette table. I win, I double my money, and I leave. I go to the cashier’s window. “Gaming is wonderful,” writes Baudrillard in Fatal Strategies, “because it is at the same time the locus of the ecstasy of value and that of its disappearance.”26

“Scusi, Signorina, Lei pensa che mi si rovina l’appetito se mangio cinque pezzi di cioccolato fondente?” (“Excuse me, Miss, do you think that I will ruin my appetite for dinner if I eat five huge pieces of chocolate fudge?”)

Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. The famous Venetian bridge called the Rialto was a hub of anti-semitism in Shakespeare’s time. At today’s Las Vegas Venetian hotel-casino, there is a nice Jewish deli called The Rialto.

The simulation of Venice in Las Vegas, its cultural-imaginary presence in the former desert of the former territory of Nevada, down to the details of gondolas, canals, and bridges.

The Rialto Bridge and the Campanile of St. Mark’s Church. The Campanile (bell tower) was last restored in 1514, when it reached its present form. It was rebuilt in 1912 after its collapse on July 14th at 9:45 A.M.

Photo © 2010 Alan N. Shapiro

- Please Follow Gerry Coulter

What is the relationship between Sophie Calle and Jean Baudrillard? Sophie was Jean’s student. Her father, with whom she had had little contact, offered her some money if she would succeed at completing her university diploma. She did not have the studious discipline to write her graduating thesis, but Baudrillard offered her a free pass. He would sign off on her degree without a substantial written work in fact having been written. Shortly after writing his commentary on her performative-photographic project in 1983 (“Pursuit in Venice”), Baudrillard went public with his own practice of photography. Although he was her teacher, it seems that he did not require much of her in the way of formalities. In an act of reversibility, she provided great inspiration to him. Sophie the follower became the leader.

“To seduce is to die as reality and reconstitute oneself as illusion,” wrote Baudrillard in his 1979 book Seduction.27 Baudrillard uses the term “illusion” within his own conceptual system of keywords, in a manner almost completely different from the signification which the word has in ordinary language. There is indeed an intersection of meaning between Baudrillard’s usage and that of everyday language: the idea of deception. According to one dictionary, illusion is “something that deceives by producing a false or misleading impression of reality.”28 For Baudrillard, on the other hand, illusion is a positive term denoting an original dual form of the world which cannot be erased or covered over, and which cannot be controlled or systematically ordered by the rational thinking human subject. What this means in the context of the dual/duel relationship of shadowing, doubling, following and tracing is that to be someone’s mirror is not to be their reflection, but rather to be their “deception” – their reverse-image, their seduction. Someone who is the same as, yet different, from me. Rather than identical or non-identical to me.

I exchanged e-mails with Gerry Coulter for about ten years. He supervised the “blind peer reviews,” version revisions, and publication of five essays of mine in the International Journal of Baudrillard Studies (IJBS). He either himself edited several of these essays, or gave me very valuable editing advice or instructions on what to change. Gerry also orchestrated the appearance of two book reviews in IJBS of my book Star Trek: Technologies of Disappearance. Gerry had understood right away that my 350-page book on Star Trek was a book about Baudrillard’s system of thought. What a book is about does not have to be matched in its title.

Gerry Coulter also encouraged me to encourage young and promising Baudrillard scholars to contribute to the journal. I have had the privilege of meeting in these last years some awesome young Baudrillard and Baudrillard-influenced scholars like Michal Klosinski, René Capovin, Samuel Strehle, and Robin Parmar, and they have published in IJBS. I have also translated two excellent essays on Baudrillard from German into American English, those by Caroline Heinrich (“In Search of the Child’s Innocence”) and Aurel Schmidt (“Only Impossible Exchange is Possible”), respectively, and Gerry published those essays. They were papers from the 2004 conference on “Baudrillard and the Arts” convened on the occasion of his 75th birthday at the “Center for Art and Media Technology” in Karlsruhe, Germany.29

I met Gerry Coulter twice in person.

The first time I met Gerry was in Stockholm, in December 2013, at the conference on “Baudrillard and War” organized by Dan Oberg at the Swedish Defense University. Gerry was the keynote speaker at the conference. It was wonderful to listen to Gerry in person and to talk with him. Gerry expressed his disagreement with my project of connecting Baudrillard’s ideas with those of other thinkers, saying that he believes that Baudrillard is singular and cannot be compared to, or combined with, others. This was a challenge to me.

Our most memorable time in person together came in April 2016 in Paris. Thanks to the generosity of Primavera de Filippi, I was able to organize a conference on “What is hyper-modernism?” which took place at the Centre d’Etudes et de Recherches de Sciences Administratives et Politiques (CERSA) in Rue Thénard. Several friends of mine – like Robin, Michal, Alexis Clancy, Cristina Miranda de Almeida, Stefano Mirti, and Regan O’Brien – participated in the hyper-modernism conference, either presenting papers or doing a creative choreographed performance (Regan). And Gerry Coulter was there too – introducing his theoretical analysis of Baudrillard and Zizek on terrorism. The entire group (and a few very nice French people) had intense discussions which lasted from 9 A.M. to 9 P.M. My conversations with Gerry were illuminating and enjoyable. He praised my presentation on the history and future of the concept of hyper-modernism. But he also questioned the appropriateness of using the term “hyper-modernism” in cultural studies or historiography, arguing that it had already been co-opted by “technophile transhumanists.” This was a dare or disputation.

It was a magical experience to listen to Gerry’s wit and to interact with his playful and lucid personality. Gerry had to fly back to Canada that evening. The rest of us had a fantastic dinner in a Cantonese Chinese restaurant, and then spent the next two days together going to bookstores and hanging out in the Latin Quarter.

This day spent together with Gerry in Paris is a very joyful and meaningful memory. I was looking forward to continuing and deepening our friendship. I was sure that it would happen.

To put into words what Gerry Coulter “truly” means to me is a most daunting task. From about age 18, I was drawn to social and cultural theory. I started to read Baudrillard intensively in the late 1970s. He was the only thinker who explained to me the world in which we are living. Baudrillard was not highly regarded or respected by my friends, and by my intellectual-academic-political colleagues and acquaintances. I was lost in the wilderness. There was no one with whom I could talk about Baudrillard. Then I noticed that Gerry Coulter had given birth to the International Journal of Baudrillard Studies. This was thrilling for me and the opening of the horizon. I owe Gerry an incomparable debt.

In spite of the tragedy of death coming at the very young age of 57, Gerry Coulter made a great achievement with his life. I think that his work in cultivating and nurturing his baby IJBS has completely changed the perceptions that we have of Baudrillard in the academic and cultural worlds. Since Baudrillard is one of the most eminent and prescient thinkers of our time, and he has been misunderstood by so many commentators, this is a great achievement. (Paradoxically, Baudrillard wanted to be misunderstood.)

I shall miss Gerry greatly. I grieve. I mourn. I am very grateful for the beautiful memories which I have of Gerry, both cool (e-mail) and hot (in person).

Please follow Gerry Coulter. Shadowing and doubling. Following and tracing.

This is a query, an invitation, an interrogation, a silhouette, a game with vestiges.

NOTES

1 – Gerry Coulter, “Art” (pp.20-22) and Alan Cholodenko, “Photography” (pp.155-157) in Richard G. Smith (ed.), The Baudrillard Dictionary (Edinburgh University Press, 2011).

2 – Jean Baudrillard, The Conspiracy of Art: Manifestos, Interviews, Essays (Semiotexte, 2005).

3 – Gerry Coulter, “Art” in The Baudrillard Dictionary; p.20.

4 – Ibid.; p.21.

5 – Jean Baudrillard, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place (Indiana University Press, 1991); Paul Virilio, Desert Screen: War at the Speed of Light (Bloomsbury Academic, 2005).

6 – See Richard G. Smith’s entry on “Artists” (pp.22-23) in The Baudrillard Dictionary; Jean Baudrillard and Jean Nouvel, Les objets singuliers: Architecture et philosophie (Calmann-Levy, 2000); Jean Baudrillard, “The Matrix Decoded: Le Nouvel Observateur Interview,” International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, July 2004.

7 – Baudrillard, The Conspiracy of Art; p.80.

8 – Ibid.; p.89.

9 – Jean Baudrillard, “Photography or the Writing of Light,” in CTHEORY, April 2000.

10 – Baudrillard, The Conspiracy of Art; p.101.

11 – Gerry Coulter, From Achilles to Zarathustra: Jean Baudrillard on Theorists, Artists, Intellectuals & Others (Intertheory Press, 2016).

12 – Jean Baudrillard, “Olivier Mosset: The Object that is None” (pp.138-140) and Baudrillard, “Enrico Baj, or Monstrosity Laid Bare by Paint Itself” (pp.141-142) and Baudrillard, “The Transparency of Kitch: A Conversation with Enrico Baj” (pp.143-154) in Gary Genosko, ed., The Uncollected Baudrillard (SAGE, 2001); Olivier Mosset and Baudrillard, Olivier Mosset (Distributed Art Publishers, 1999); Enrico Baj and Baudrillard, Enrico Baj: Transparence du kitsch (L’Autre musée) (Galerie Beaubourg, 1990); Baudrillard, L’Autre: Luc Delahaye (Phaidon, 1999); Baudrillard, “Charles Matton ou l’illusion objective” in Charles Matton (Editions Hatier, 1991); Baudrillard, “Please Follow Me” in Sophie Calle, Suite venitienne, Baudrillard, Please follow me (Seattle: Bay Press, 1988); Baudrillard, “Pursuit in Venice” in The Transparency of Evil: Essays on Extreme Phenomena (Verso Press, 1993); pp.156-160.

13 – Gerry Coulter, “Sophie Calle” in From Achilles to Zarathustra; p.50.

14 – Baudrillard, “Please Follow Me” in Bay Press book; p.77.

15 – Calle, “Suite venitienne” in Bay Press book; p.18.

16 – Baudrillard, “Please Follow Me” in Bay Press book; p.76.

17 – Calle, “Suite venitienne” in Bay Press book; p.22.

18 – Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays (Vintage Press, 1955); p.10.

19 – Baudrillard, “Please Follow Me” in Bay Press book; p.77.

20 – Calle, “Suite venitienne” in Bay Press book; p.26.

21 – Baudrillard, “Please Follow Me” in Bay Press book; p.83.

22 – Calle, “Suite venitienne” in Bay Press book; p.42.

23 – Baudrillard, “Please Follow Me” in Bay Press book; p.83.

24 – Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas (The MIT Press, 1972).

25 – Jean Baudrillard, Fatal Strategies (Semiotexte, 1990); p.50.

26 – Ibid.; p.53.

27 – Jean Baudrillard, Seduction (St. Martin’s Press, 1990); p.69.

28 – Random House Webster’s College Dictionary (1995 edition); p.671.

29 – All Karlsruhe conference lectures were collected in the book: Peter Gente, Barbara Könches und Peter Weibel, Philosophie und Kunst: Jean Baudrillard, Eine Hommage zu seinem 75. Geburtstag (Merve Verlag, 2005).

From 2015 to 2017, Alan N. Shapiro was Visiting Professor of Transdisciplinary Design at the Folkwang University of the Arts, Essen, Germany. His book publications include: Star Trek: Technologies of Disappearance (AVINUS Press, 2004); The Technological Herbarium (editor and translator) (author: Gianna Maria Gatti) (AVINUS Press, 2010); Software of the Future (Walther König Press, 2014); and Transdisciplinary Design (Passagen Verlag, 2017). He currently teaches “design and informatics” at the Lucerne University of Science and Art, and media theory at the Bremen Art University.