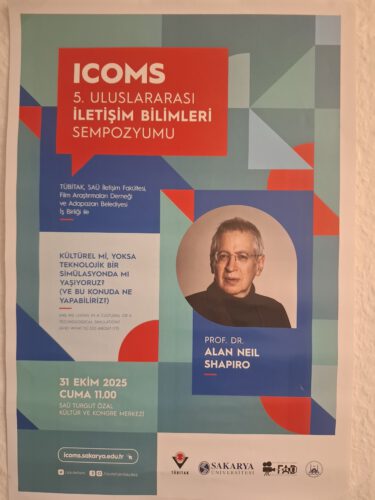

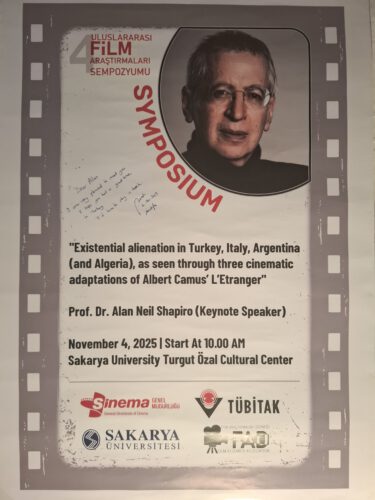

On October 31, 2025, I was a keynote speaker at the conference on “Media and Communication” at the University of Sakarya, Turkey. On November 4, 2025, I was a keynote speaker at the conference on Turkish cinema at the same university. Below are excerpts from the two lectures.

Dear Prof. Shapiro,

Mustafa and I would like to extend our heartfelt thanks for your deeply inspiring keynote during the International Communication and Film Symposiums. Your lecture was, for many of us, one of those rare intellectual encounters that resonate far beyond the event itself — one that quietly reshapes how we see the world, technology, and the human spirit.

Your reflections on cultural and technological simulation profoundly affected me personally. They compelled me to reconsider the trajectory of modern civilisation — not merely through the lens of progress and innovation, but through the ethical and existential costs of our accelerated digital environment. I was particularly struck by your distinction between technological and cultural simulation, and by your argument that before it was ever a technical phenomenon, simulation was already a cultural condition. This insight helps us understand that we are not simply heading toward a simulated future — we have long been living within it.

That realisation struck me deeply. It made me recognise that we are drifting in a state where meaning is slowly dissolving, where we have lost control of time itself. In this rapid flow, we no longer truly see or understand one another; we rarely face our own mirrors. Quantity replaces quality, visibility overshadows depth, and the image becomes more valuable than the essence. Your lecture became, for me, not only an intellectual experience but also a moment of self-reflection.

In the following days, I revisited your writings with special attention to how your ideas converse with postmodern media theory and philosophy. In my own research on film, media, and pedagogy, I often explore the intersections of image, perception, and ideology. Reading your work illuminated new ways of understanding film adaptations of Albert Camus’s L’Étranger — from Visconti’s Lo Straniero to Zeki Demirkubuz’s Yazgı — not merely as artistic interpretations of existential alienation, but as cultural simulations of meaning, morality, and identity. Your conceptual vocabulary, especially your treatment of hyperreality and post-truth, opened an entirely new layer of interpretation for me: cinema as a laboratory of simulation, where truth and its image continuously exchange places.

Your work bridges critical theory and lived ethics in a way that feels both rigorous and profoundly humane, and I have already begun to integrate some of your ideas into my reflections on film pedagogy and digital literacy.

Most of all, I was deeply moved by the humanistic tone underlying your intellectual vision. Your call is not for a war against technology, but for a renewal of humanity through creativity, awareness, and ethical imagination. This message resonates strongly with me. I share your conviction that our task as educators and researchers is to find ways — both poetic and practical — to help humanity stand upright again, to think and feel critically within the technological storm we inhabit.

Please accept my sincere admiration for your work and the generous spirit with which you share it. Your ideas have become a lasting source of motivation for me, and I will continue to follow your writings and lectures closely.

With great respect and gratitude,

Serhat Yetimova

Professor of Cinema and Intercultural Communication

The first lecture was called:

Are We Living in a Technological or a Cultural Simulation?

(and what to do about it)

Are we living in a technological or a cultural simulation?

Billionaires like Elon Musk, whose main interests are making money and developing advanced technologies, and futurist philosophers like Nick Bostrom, who focus heavily on technology, believe that we might be living in a technological simulation created by a super-evolved alien civilization somewhere in the galaxy. This civilization could have achieved Artificial General Intelligence, built super-powerful computers, and developed Virtual Realities indistinguishable from physical worlds. Musk has speculated that the chance we are living in such a simulation is 99.9%. Bostrom’s thesis is known as the simulation hypothesis or argument.

Conversely, postmodern media theorists such as Umberto Eco and Jean Baudrillard argue that we live in a cultural simulation, also called hyperreality. After World War II, Western societies developed a consumer and media culture focused on television, movies, advertising, organized leisure, shopping malls, and politics as entertainment. In postmodernism, images and verbal rhetoric replace the physical reality and social facts they are meant to represent. The copy replaces the original. In a reversal, codes and models take precedence and shape daily life. The disappearance of reality does not happen through some supposed betrayal of “reality” by virtuality but through an overload of “reality” shown in high-resolution graphics. The culture of what the ancient Greek philosopher Plato already called rhetoric—defined as images and discourse—creates its own “hyperreality,” making the old, familiar reality fade away. Signs become independent and disconnected from their “referents.” Reality and the image move into each other’s spaces. Simulation replaces representation.

In science fiction movies like The Matrix, The Thirteenth Floor, World on a Wire, and Don’t Worry, Darling, the idea is shown that what we consider our physical reality—the world around us—is actually a complex, detailed three-dimensional computer simulation. The character played by Leonardo DiCaprio in Inception uses a small spinning top as his sole means of determining if he is in reality or a simulation.

The race is currently on to become the first multi-billion-dollar mega-company to develop AGI and reach the groundbreaking milestone of surpassing human intelligence with Artificial General Intelligence, which we can either celebrate or fear. This predicted event, expected within the next few decades, is known as “the singularity.” Bostrom has described it as “superintelligence.” Microsoft, as the largest investor in OpenAI, and Google, owner of DeepMind (setting aside for now the powerful Chinese AI chatbots like DeepSeek), are key contenders in this race. It serves their interests, often presented as public relations statements supported by supposedly brilliant philosophical and scientific expertise, to excite the public with the sensational, history-altering capabilities that the AGI will possess. In a sense, the idea of our reality as a technological simulation programmed by post-AGI aliens is one aspect of the hype surrounding the purported incredible breakthroughs AGI will achieve. However, it is also essential to treat the idea with philosophical seriousness and rational debate.

I suggest that the idea of reality as a technological simulation reflects an unconscious psychological projection of the situation that those discussing it have been living for decades within a culture increasingly shaped by simulation. Simulation is cultural before it becomes technological. Our simulation is both technological and cultural, but it was initially cultural. Digitalization has amplified the phenomena of simulation and hyperreality that already dominated society before the digital age. There is a growing trend for all our experiences to become more virtual, including our interactions with others. Experience is shifting toward a Virtual Reality “Metaverse.” VR and AR simulations are becoming more common. We face a crisis in democracy, often referred to as the post-truth era, driven by partisan discourse fueled by emotions, ideology, and social media, which undermines consensus on facts, truth, and science. That is, at its core, hyperreality in politics. Hyperreality offers a deep explanation of post-truth. All these cultural trends involve replacing an original with its image, copy, demagogic language, or sound bite, whether in words, statistical models, or code.

The second lecture was called:

Existential Alienation in Turkey, Italy, Argentina, France,

(and Algeria), as seen through four cinematic

adaptations of Albert Camus’ L’Étranger

One of the great novels of the twentieth century is The Stranger by Albert Camus, the French philosopher known for his existentialist views on alienation. Currently, the new film adaptation of The Stranger by François Ozon is playing in movie theaters. The Stranger has been adapted in different media by creators from Algeria, Turkey, Italy, Argentina, and France. In this talk, I will briefly interpret the five different versions to gain insight into the specific conditions of existential alienation in each of the five national cultures.

In 1999, the respected French newspaper Le Monde and the bookstore chain FNAC published a list of the “100 Books of the Century,” regardless of the language they were written in. This list was based on a survey of 17,000 readers, who were asked which books had “stuck the most” in their minds. The top book on the list was the 1942 short novel L’Étranger by Albert Camus, known in English as The Stranger or The Outsider. The work is a masterpiece of world literature. In the novella, the protagonist and first-person narrator, Meursault, shoots and kills a nameless Arab man on a beach during a hot summer, with the sun glaring in his eyes. The philosopher and author Camus, who grew up in urban poverty in Algiers, was from a family of the so-called pied noir French settlers or colonizers in Algeria. Leftist literary theorists in the tradition of post-colonial criticism have often claimed that the disregard for the life of the victim of Meursault’s crime shows that Camus was a racist. The Algerian writer Kamel Daoud even wrote a retelling of the fictional events of The Stranger, called The Meursault Investigation (published in 2013), recounted from the viewpoint of a different main character, Herun, who is the brother of Meursault’s victim. The dehumanization of Camus’ Arab, who is gazed upon as “other” to the white Frenchman, is challenged by giving the Arab the human name Musa.

Camus’s book initially gained fame not as a commentary on society or politics but as an expression of his philosophy of absurdism and as a portrayal of what I will call “existential alienation.” Existential alienation is a deep feeling of estrangement from oneself, others, and the world. It’s linked to the idea that life has no inherent meaning. Belief systems, such as organized religion, provide a social collective with automatic meaning; however, they are inauthentic because they do not encourage individual conscious reflection. The person living through existential alienation feels disconnected and like a stranger in their own life. Yet, paradoxically, this can lead to meaningful self-discovery. While waiting for his execution at the hands of the French colonial judiciary at the end of the story, Meursault achieves precious insights and clarity about what he truly values.

The categorization of works of literature and art into existential and political concerns often creates a divide between exploring the universal human condition and focusing on discontent or oppression within distinct historical, cultural, or economic contexts. Am I struggling because human existence is inherently tricky, or is it because the society I live in is particularly terrible? But what if this two-tiered hierarchy or binary opposition, so to speak, between nature and culture is preventing us from understanding how particular cultures and individual experiences of alienation are connected? Instead of a dualism between contemplating the human condition and grasping specific historical circumstances, I propose a different model in which analyzing an artifact, such as a novel or a film, becomes an investigation of a singular culture through the subtle differences and details of how the artistic creation depicts the critical ordeal of alienation.

My goal in this talk is to explore how existential alienation uniquely manifests across five different national cultures: Turkey, Italy, Argentina, France, and Algeria. I will do this by examining five distinct artistic representations of The Stranger. For Turkey, this is the 2001 film adaptation Yazgi or Fate by independent director Zeki Demirkubuz. Italy is represented by the 1967 film Lo Straniero, directed by filmmaker, theatre, and opera director Luchino Visconti, starring the renowned actor Marcello Mastroianni as Meursault. Speaking of opera, Argentine composer Cecilia Arditto Delsoglio created Der Fremde, a version of Camus’s work featuring a strong musical element and dramatic roles sung by performers. This piece had its world premiere in Mannheim, Germany, in 2024. The impressive cinematic adaptation L’Étranger by François Ozon, shot in black and white, was featured in September 2025 in the main competition of the Venice International Film Festival, where it was nominated for the Golden Lion. An insight into existential alienation in Algeria under French colonial rule in the late 1930s can be gained from an interpretation of Camus’s classic literary novel itself.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.