Nicola Toffolini interviewed by Alan N. Shapiro

I interviewed the Italian artist Nicola Toffolini in Bologna, Italy. I spoke in English, and Nicola spoke in Italian. I have translated his comments into English.

Alan N. Shapiro: Since about the year 2000, you have been doing exhibitions of your artwork. How did it come about in your biography that you came to understand that you are an artist?

Nicola Toffolini: My family wanted me to do something to prepare myself to earn money. But at a certain point I realized that I could not do that. I started to study art and graphic design. I went to the school of fine arts in Venice in 1995. What interested me about art from the very beginning was that I could do work at the intersection of many different fields of knowledge. It brought me into contact with knowledge of many kinds.

AS: Did you have teachers or mentors at the fine arts school in Venice who especially influenced you?

NT: My teacher of painting. His name was Luigi Viola. From him I learned a conceptual vision. It wasn’t necessarily just about techniques. He taught me that art is related to ethics, that I want to find my truth, and my artwork should have a relationship to this truth. Art should be done with a sense of responsibility. Around the same time, I became interested in theatre. Since the mid-1990s I have been pursuing both theatre and art in parallel. The two activities involve fundamentally different forms of relationships with other people. In the theatre I have a direct encounter with the other, and it is a relationship of complete equality. In my artwork, I am designing things, proposing things, and other people who are specialists carry them out.

AS: That makes me think of two different meanings of the word ‘performance’. In the theatre, you are doing the performance. In your artwork, the technical specialists who construct the artefacts that you have designed are performing the artwork, in the sense that they are implementing the design.

NT: I work with a lot of other people. It is a collaboration. I need technical consultants. I do not have any specific technical education. I don’t know electronics systematically, only in an approximate way. In some projects, I become involved and fascinated with the technical aspects, and I work side-by-side with the specialists and I learn a lot of things. But mainly I work with intuition. I start from certain intuitions, and I try to find a poetic solution.

AS: What was your first installation?

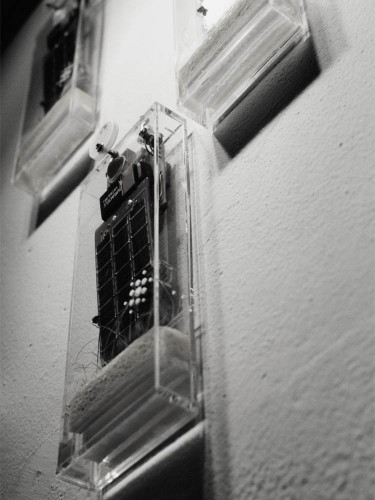

NT: My work with plants and with nature began in 1997 with the installation “Lussureggiante prato verde della lunghezza lineare di un metro e dieci grilli.” Lush green grass of the linear length of one meter and ten crickets. There were ten plaxiglass containers of ten centimeters in length each. There were small lawns and seeds of grass. The containers in the exhibition space were sound machines which reproduced the singing of crickets in a meadow. A person enters the space and influences the sound of the crickets. The visitor becomes a part of the artwork.

AS: If we look at many of your works, there is something from nature, there is something technological or engineered, and there is often an important role for the human participant. Can you say something about the relationship among these three elements?

NT: The question is very difficult and I do not have a single answer. Nor is there any clear position taken in my artworks. The concept of nature that we have is the result of centuries of evolution and history. It is not univocal. Nature for me is very ambiguous, and we are currently experiencing a strange passage. Nature is one of those words which seems to refer to and include a lot of things, but in fact it really says nothing. Yet we continue to use it. We speak more and more about nature, but it disappears beneath our words. Maybe our concept is completely wrong. Nature has never been so far away as it is today from our actual perceptions. It has become just a screensaver on a telematic device. We imagine nature in some ideal way, but this has very little reality. It is an abstract paradise. What I like to do is to bring out contradictions, to make provocations.

AS: We seem to be obsessed nowadays with universal technology, universal nature, and universal information. Perhaps we are destroying the chance to have direct experience. Is the suffering of the plant a metaphor for disappearing direct experience?

NT: This is an aspect. We have an enormous quantity of information, including intimate information. We are bombarded with information on the Internet, in our society, and we are suffering at the hands of technology and living in submission to its time. Yet we try to maintain a certain equilibrium by often believing in a unique horizon, the goal towards which we believing everything is headed right now. What interests me with the plant is the object in vitro. Isolate the plant. Establish a certain set of initial conditions, a series of parameters. The result is conditioned. The plant reacts to the circumstances, and tries to grow within these conditions. So the paradox is that I continue to refer to a concept of nature – or other people see me as making artworks about nature – yet I am working with in vitro controlled parameters which are really quite far from nature.

AS: Is your work political?

NT: I don’t believe in anything. If there is something that I believe in, it would be in exactly that: nothing. The nothing. [I don’t think that Nicola Toffolini believes in nothing in the conventional sense of the meaning of that word. I think that he believes in nothing in Flaubert’s sense of nothing, le rien, Flaubert’s goal of writing a book about nothing, as he said. It was Flaubert’s love of writing itself, for Nicola the love of the hybrid nature / high-tech in vitro sculptures that he makes. — AS] I try to articulate questions. I look for contradictions, so perhaps this is a political aspect. A non-explicit politics. I try to go one step further in the analysis. “Su la testa versus Giù la testa” is a very cynical work. The plants are forced to grow in an artificial paradise. Temperature and water are controlled. The plants can do nothing else but grow. Something else that I might be able to say that I believe in is a sense of limits, for example, ecological limits.

AS: Do you think that the ecological movement has an idealized version of nature?

NT: We are living in a system that has already accomplished a lot of evil. And we are stuck in it. It is way beyond the understanding of any single individual. Changing a few things today or tomorrow won’t really save us from the vast ecological catastrophe which has already taken place, or the vast financial catastrophe. Yet there is a certain slow learning process that can happen over decades. There is no one solution. We have to go on living. I doubt if we can go back. We have to live in an experimental and conscious way. The way we consume. The way we do commerce. We cannot continue to live the way we are living now, this standard of living. We are used to not thinking, and not thinking beyond the needs of today. In Italy, no one really thinks about tomorrow. We have to change this. This is not a responsible way to have a relationship to others.

AS: There is a very bad economic crisis in Italy. And a political crisis that is perhaps more of a pseudo-crisis.

NT: Until now, everyone has pretended to not see anything. The distance of politics from everyday life, the distance from any real participatory democracy. People did not pay attention. They always took the attitude to leave it up to someone else. Nobody did anything. For twenty years. It was left in the hands of this so-called ‘magical personality’ at the top. A populist with banal ideas. Italy is a strange country. If things are going well for a certain period of time, then everyone here prefers to disappear into apathy. This attitude returns again and again.

AS: Would you like to have an identity that is more than Italian? Do you feel European or something else?

NT: Yes. I don’t really believe in borders. There is a tendency in Italy to blame problems on foreigners, on immigants. It would be better for us to leave this provincial attitude behind.

AS: Design plays a very important role in your work.

NT: I design. That is the main thing that I do. I take the time to design in a slow way. My works finish at the stage of the study. Others achieve the realisation. Only a few of the designs get realised as projects. Many of the designs are like taking walks. They express my precession of thoughts. It is not necessary for me to realise them as art projects.

AS: So the heart of the creativity happens during the first phase. This is not necessarily art, but perhaps something else. Has the gallery system in Italy been helpful and supportive to you?

NT: I have had negative experiences with some galleries. Sometimes I felt a certain lack of mutual respect. I would like the gallerist to be interested in the work, but instead they are usually interested only in the money. Then it becomes work like any other kind of work. I have a somewhat romantic idea of ‘the research’ (la ricerca). The research goes beyond what the system calls art. The research is a risk, it is part of a journey. I don’t want security or money. What I really want is to continue my ricerca. But it’s true that I also have a lot of friends in Italy who have helped me with my work. And various agencies (aziende) within the Italian civil society. Paradoxically, the larger works that were brought to fruition were financially supported by institutions which have nothing to do with art. Cultural associations. Small groups. This comes not from the mainstream, but from the base of society.

AS: Perhaps the problem comes not only from money and galleries, but also from the idea of art that our society has, the idea that art is a separate sphere, a separate activity, that there are individuals who are ‘professionals of creativity’. Is it different for you in the theater?

NT: Working in the theatre means working live, with the pubic present, having a direct relationship, unmediated. This relationship is political. The people who go to the theatre have already made a choice to be more disposed to a meaningful interaction. In some projects that we have done in the theatre, the public is very involved. The world of art is different. There is no immediate or direct exchange. What really interests me in my so-called art work is the coherence of my research. Just now I took a break for two years. I was getting used to doing things in a certain way. The works that I will start next year will be very different than before. I want to go on with my research. I might make a mistake, but if I make a mistake, I want to be able to admit that I made a mistake and have the freedom to go back and correct it. Our society seems to offer too little opportunities to do that. I want to grow, and I need time in order to do that. I want to place myself continuously into question.

AS: There is perhaps something like a human right to make a mistake. Can you tell us something about your new cycle of work.

NT: I like to play with energy. The energy provided by the sun and water. The natural circulation of water. The idea is sort of to have installations or scupltures which surround these energies. The artwork situates itself halfway between this energy and a particular kind of technical praxis. Capture the energy and channelize it in a way that something is achieved or brought to functionality. It will be at the same time something useful and a strange sculpture. I am moving in the direction of working on smaller and more subtle things. I want to achieve a greater sublimation of the technology and the formal method. Reduce the footprint of the computer and of the technology. Be more efficient and more poetic.

AS: You live in Florence, Venice, Udine. What is it like to live in special places like that?

NT: You wake up in the morning, and you ask yourself, what I am doing here? It is a strange emotion, to be in the middle of all this history. You start to live in a different order of time.